Freakonomics’s two-part radio and podcast episodes called “Does Advertising Actually Work” (Part 1, Part 2)has raised a few eyebrows from agencies and clients alike. It’s one thing for a research scientist to present at an academic conference saying ads are a waste of money. It’s another when real experiments with real brand advertising budgets are brought to a mainstream media program consumed by a lot of C-Suite executives.

In the series, host Stephen Dubner and an array of expert sources, including his original Freakonomics book co-author Steven Levitt, discuss a number of experiments suggesting advertising doesn’t work. Those presented include seemingly startling experiments with paid search ads for eBay and Procter & Gamble that assert you can cut your paid search budget to zero and it has no effect on sales.

Part 2 is the primary focus of my ideas here. It’s the one focused more on digital advertising. Part 1 focused on television advertising. Both can be listened to or read, via their transcripts, by following the links here to the Freakonomics website.

As the pieces point out, there are some interesting stakeholders and interesting outcomes in all this, if those C-Suite executives buy-in to the headline notion presented. If ads don’t work, let’s cut our ad spend, right? Or let’s move that ad spend to other marketing tactics that do work. I’m an earned and owned segment guy, so you might think that sounds great to me!

But it doesn’t.

Why the Advertising Doesn’t Work Assertion is Flawed

The experiments presented in the piece (at least the digital one), by researchers like Steve Tadelis of the Haas School of Business at the University of California at Berkeley, have a bit of their own bias that isn’t really accounted for. Tadelis convinced eBay to run an experiment where they turned off all paid search on branded, then unbranded terms, to see if it had much effect on sales. Neither of the two experiments showed a change.

Quite useful and insightful conclusions were presented about branded search (in my opinion). The conclusions there align with what I’ve told clients for years: “If you’re already winning branded searches organically, also paying for ads there is a waste of money.” Tadelis says in the episode, “The analogy in my view of brand keyword advertising is handing out the coupons inside the restaurant.”

But overall, Tadelis’s assertion based in the eBay experiments was that paid search advertising doesn’t lead to much sales lift at all. The conclusion by C-Suite folks is most likely to be to kill paid search ads.

However, think about the data set: Tadelis was working with eBay, a massive online retailer that spent $100 million or so on paid search advertising. He wasn’t experimenting with a challenger brand, a regional business, a startup hoping to drive some efficient traffic to a new offering. He was testing this hypothesis on the other end of the bell curve.

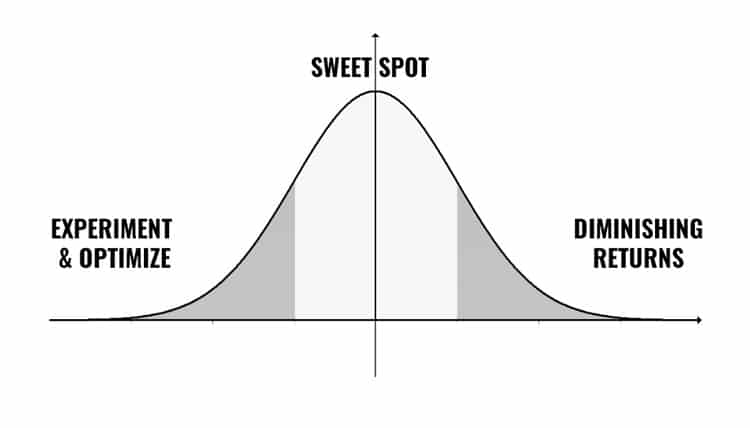

My hypothesis in response is that there are different kinds of paid search success based on a company’s evolution through search maturity, market awareness and budget.

Think of a standard bell curve. For paid search advertising, new companies that don’t have a lot of budget and throw $10 per week at paid ads don’t wind up with enough exposure or bid wins to show a good return on investment. As they experiment and optimize, they grow budgets and sophistication and move into a sweet spot where paid search advertising is quite productive and efficient.

However, as a brand’s growth creates a tipping point of awareness and trust, coupled with stronger organic rankings that should accompany that growth, paid search investment begins to slide down a slope of diminishing returns. In other words, paid search spend is probably not the best use of dollars for eBay, Amazon, Wal-Mart, Target and other category leaders. They’re likely ranking well for the same terms organically and most searchers don’t click on ads anyway. (There’s plenty of research to back this assertion.)

My answer to Tadelis’s experiments, and even those done with Procter & Gamble who killed a $200 million ad budget as an experiment with similar results, is your assertions work only for the one-percent on the far end of the curve. They don’t apply to companies in the sweet spot.

I’d be tickled if anyone would love to pick up that hypothesis and test it.

Certainly, I recognize the greater challenge the Freakonomics episodes present — It’s hard to prove advertising works. A fair amount of advertising doesn’t. But a good portion of it does.

And if, when we question advertising and its effectiveness, we compare apples to apples, we’ll probably be a lot better at finding an answer everyone can benefit from.

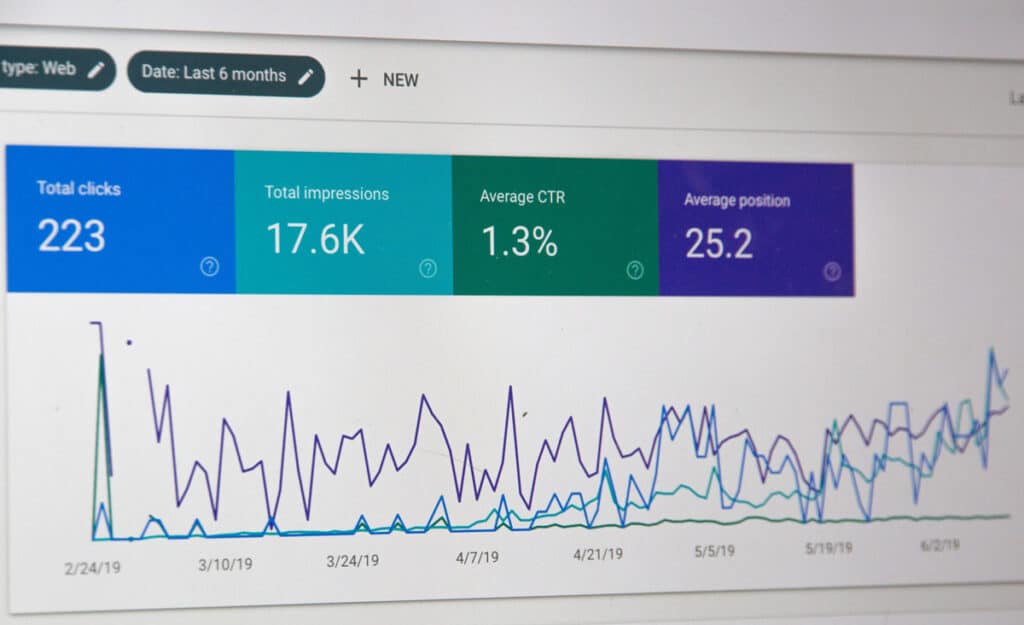

Note: Photo by Stephen Phillips – Hostreviews.co.uk on Unsplash